Courtland Place

Rainier Valley, Seattle

“An intrepid storyteller, Fels has framed his project with stories, a powerful and ancient means of creating connections.”

– Barbara Johns, Chief Curator, Tacoma Art Museum

In 2002, Fels was selected for the inaugural run of Arts Up, a unique project initiated by the City of Seattle. Given great latitude to develop a project, a handful of artists were placed with communities. Fels worked in Courtland Place, a small area in the city’s Rainier Valley, long plagued with drug problems. He spent several months looking and listening, attending community meetings, tatlasng with residents, and getting a sense of the neighborhood.

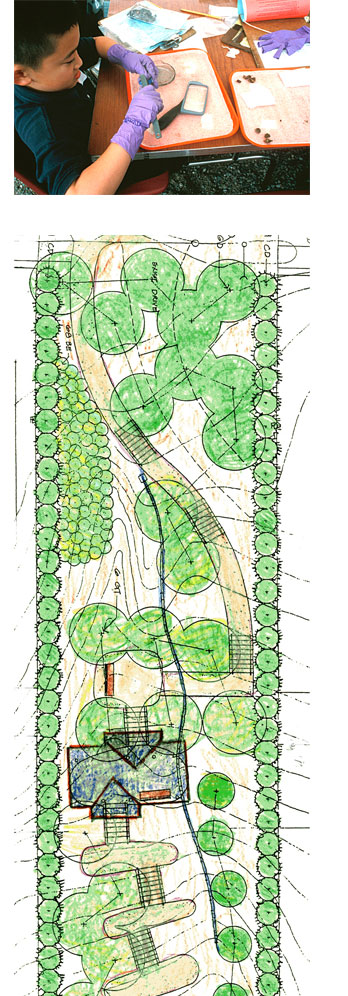

From these encounters he learned that the community wished to construct a ‘hillclimb’ following a dirt path to the Mt. Baker neighborhood on Lake Washington. Conversations and research established that the path had been used for at least 75 years, though recently many considered it unsafe. The residents asked Fels if he could design an artful hillclimb that would include a gathering place for the community. Fels proposed the project to the city and was funded to develop the idea. He engaged noted landscape architect Richard Haag to work with him. The neighborhood is currently fund-raising to allow for the full construction of the project.

Older residents mentioned that the neighborhood had once been the site of a garbage dump. It seemed that the dump had been sited on a large tract of land currently occupied by a retail development. Fels decided that treating the area as if it were a midden would produce interesting historical insights about the neighborhood- what was learned could then be incorporated into the hillclimb. He contacted the Burke Museum of Culture at the University of Washington, and spoke with Peter Lape, professor and Curator of Archaeology at the museum. Lape was enthusiastic about doing an urban dig, a process never before attempted in Seattle.

4Culture provided the necessary funding, and Fels partnered with two other institutions – the Rainier Valley Historical Society and its director Mikela Woodward, and nearby John Muir Elementary School. Fels arranged with the school for two 4th grade classes to carry out the dig, with a support staff of specialists, under the guidance of Peter Lape. Lape had the excavation registered as an official archaeological dig with the state. Fels and Woodward spent two months in the early fall meeting with the 4th graders, exploring the idea of history, working with students to imagine how the neighborhood might have been sixty years before, and helping them understand how the dig would progress. Alumni who decades before had attended the elementary school were contacted, and came to be interviewed by the students. The oral histories were recorded and transcribed for the historical society.

Fels arranged for the city transportation department to open two holes in a street in Courtland Place, and have it cordoned off for the dig. The Burke Museum supplied two large tents, all the necessary tools and material for surveying, weighing, recording and cataloguing the finds, as well as fifteen archaeologists and doctoral students. The 4th graders, with their archaeologist ‘assistants’, worked in teams and the dig moved slowly forward, the dirt being sifted gingerly. By week’s end, each of the sites had yielded a great deal of material: jars, bottles, pieces of wood, metal, cloth, and ceramics. On the final day the holes were covered over and Lape filed a report on the finds with the state.

Fels and Woodward continued to work with the 4th graders to consider and research what they had found, what it might tell them about the neighborhood. As they had done before the excavation, the kids made drawings and wrote about how they imagined the neighborhood to have been – having completed the dig, they had many new clues.

Fels and Woodward curated an exhibition including finds from the dig, the children’s drawings and writings, and holdings from the historical society’s collection. The exhibition was mounted in the display cases in the historical society. Curators from Seattle’s Museum of History and Industry visited the little exhibition, and asked if it could be enlarged and remounted at their museum. They wanted it for an area where 4th and 5th graders assemble on school tours of the museum. Fels and Woodward worked with the chief installer at MOHAI to give the visiting classes a sense of how children could investigate and understand local history.

Fels used a story gathered by 4th graders for the first phase of the hillclimb construction. Long ago, neighborhood kids used to climb trees (now all cut down) to watch for people coming up the hill towards their fort. He created a ‘periscope tree’, installing it at the top of the path. A large metal sculpture, it has a working periscope within, which scans the streets below. The tree, the dig, and the plans for the hillclimb all grew from discussion – talks with residents, professionals and children. Arts Up funded Fels to hang out in the neighborhood; the residency provided the ideas that he parlayed into action. The largest challenge was coordinating with the large number of people and institutions ultimately involved –but having them all take part in the project proved enormously synergetic. With more involvement, more opportunities presented themselves. In turn, and certainly not surprisingly, the project had a distinctly salubrious effect on the neighborhood itself.

Having thoroughly enjoyed their collaboration, Fels and Lape have now embarked on a larger project involving several scientists and university investigators. Waterlines will mark the natural shoreline of Puget Sound hidden beneath Seattle, which for a century has been filled, channeled and reoriented.