Central Asia

2019

In 2019, I had the superb good fortune to be named a Fulbright Scholar in Uzbekistan. Long fascinated by Central Asia as E/W nexus of trade and culture, I was thrilled to be going there. In preparation I read as many books and journal articles I could digest on cultural and regional history, anthropology, art history, geography and political economics. Patricia and I set off for Tashkent in September.

We found people to be generous and welcoming, it was extremely interesting to be living in the capital city and fascinating for us to travel in the region. Unexpectedly, I spent two months of meetings, writing letters, and making calls. I had been encouraged by the Director of the Savitsky Museum to try and gain access to their closed archives.

She warned me, however, the answer would very likely be no. I ended up needing permission from a wide loop of officials, bureaucrats, embassies, and interested institutions in order to spend time in the museum archive in Nukus, far out in the steppe. Ultimately, I was successful, and flew there from Tashkent for a week, for my first look at the works on paper stored there.

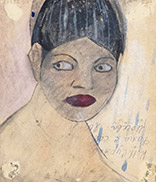

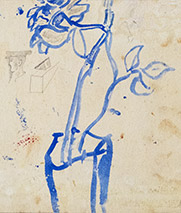

Trained as an artist, Igor Savitsky came from Moscow to isolated Nukus as a young man to illustrate the finds from a Russian archaeological dig and made it his home for life. In the 1960s he began making furtive trips to Moscow ferreting out Soviet avantgarde and post-avantgarde works. Stalin had declared this art subversive, and therefore illegal to create, store or collect. Savitsky found artworks hidden in attics, under floorboards and used as building material. From descendants of the artists, he purchased and borrowed art that had been long kept out of view, and secretly brought it to Nukus by train.

The Savitsky Museum holds 36,000 Soviet works on paper, produced around a century ago. Hardly any were exhibited by the outlawed artists while they were still alive, and even less have been seen publicly afterwards. I made six, week-long forays to Nukus, spending 8 hours each day in the graphics archive. I was told that only Savitsky had ever spent this much time looking at the work.

The work on paper in the museum collection includes sketches, drawings, journal jottings, posters, and prints, often in large numbers from a single artist, sometimes done on both sides of the paper. Savitsky collected in-depth the work of individual artists and called his way of collecting archaeological. As with a dig, this makes it possible to study the development of an artist’s process over time.

Savitsky purposely collected work by little known, unrecognized, as well as unknown artists, feeling that otherwise the pieces he’d found wouldn’t survive, and the world would never see them. I was greatly touched by my time in the archive, and felt a deep connection with the artists, many of whom died for making their art. It was very moving to be engulfed by the works on paper that Mr. Savitsky collected, an experience I will never forget.